For one week in February, I went to Arizona to visit Aria, a poet and my best friend of 16 years. I listened to folksy western music with “desert southwest vibes” to carefully build nostalgic anticipation for a place that is very easy to romanticize.

At Phoenix Sky Harbor Airport — “America’s friendliest airport” — I saw a sign above the water fountain that said “water is life” and thought about that one sketchy proposal to desalinate water pumped in from Mexico to combat future water shortages in the state. At the airport gift shop, I bought Chex Mix and popcorn covered in prickly pear cactus syrup.

Sedona

The trip began with a night drive north from Phoenix to Sedona, a town nestled in red rock country, a pit stop for adventurers and those seeking to experience the area’s hidden spiritual offerings (i.e., vortexes). We drove into downtown and noticed the silhouettes of giant rock formations flanking the car — massive, dark, and unknown. In daylight their rusty sediment layers would be beautiful, but in darkness I felt a megalophobic awe. Our first day, we had our auras read by a lady who seemed a bit frazzled. Both auras were yellow. The chakra analysis that came within my 13-page report said most of my chakras were flowing fine that day, except for my third eye — the energy center that governs intuition, spiritual connection, and trusting my senses and gut.

We visited the Center for a New Age, the mecca of Sedona’s touristy, spiritually inclined souvenir shops. Their selection was vast: geometric crystals and smooth stones of every color promising relief for various mental ailments, purple scarves adorned with crescent moons and stars, artwork depicting the spirit animal of every zodiac sign, bronze murtis of Hindu god(desse)s and statues of Buddha and bodhisattvas, and, most strangely, a traditional Nepali khukuri behind a glass case. The absurd orientalism of it all sat quietly in the back of my mind, but my giddy enjoyment and wonder won out.1

Across the street from the Center was Tlaquepaque village, a walkable shopping center built in the 1970s and designed to look like a traditional Mexican village. The buildings were plastered with stucco and the stores, restaurants, and galleries gathered around flowery plaza squares with fountains in the middle. It was a thrill to walk up and down the stairs, through the alleys and archways, enjoying a pedestrian-only area in the middle of town. It hit me that Sedona, with its curated playgrounds and new-age souvenir shops, felt like a theme park. Maybe that was the only way for people to process the stunning beauty of the natural world in which the town occupied.

Nothing felt manufactured about the hikes. The sky was a sharp azure and the dirt was a deep rust red. The vegetation was thick with agave and prickly pear cactus. Rock formations towered above us at Devil’s Bridge, where I crab-walked down steep stone steps on the way back. At one point on Jordan trail, we stopped walking, and once our shoes stopped crunching against the ground, I realized how utterly silent the world was. Save for the occasional bird sound, the air held a quietness that I never experience in New York. It was so quiet that the air felt heavy, like a blanket gently wrapping me up.

The buttes and canyons surrounding us had formed more than 250 million years ago. For a moment I forgot the planet was even that old. Sedona’s red rock formations are older than the mountains (the Himalayas) that overlook the city my parents grew up in — they began to form only 50 million years ago; are still forming. Both geologic phenomena pale in comparison to the fact that the oldest rocks forming the mountains (the Appalachians) of my home state are more than one billion years old.

One night, we stargazed. (The stars are around 15 billion years old.) At some point in history, in cities and towns, people stopped being able to see the stars. I wonder how much it disoriented us. With the help of an app, Aria and I identified Orion, Aries, Taurus, Cassiopeia, the little and big dippers, and the planet Jupiter. The moon was waxing and shone so bright it might have overshadowed some dimmer stars.

On the drive out of Sedona, we stopped at Montezuma Castle, a collection of cliffside cave dwellings that Indigenous Americans (the Sinagua people) inhabited from 1050 to 1400. They had nothing to do with the Aztec but later, white explorers thought they did, hence the name Montezuma. I read a sign about the berries they used for soap — berries that got sudsy when you wet them — and thought about how deeply detached from nature, from the functions of plants, we are today. Around 1400, the cave dwellers left the area. They weren’t driven out, as one might assume. They may have been responding to changing weather patterns, soil quality, or signs in the sky. Some Hopi and other tribes’ descendants of the Sinagua believe they were called spiritually to move on and away.

Saguaro

People, myself included, often remark on the sheer variety of differing landscapes that exist in this country, but we don’t really consider that this was never meant to be one country. On the drive down from Sedona to Tucson, the landscape changed. The rusty rocks of Sedona ceased to exist and were replaced by rolling brown hills dotted with shrubs, which reminded me of New Zealand’s south island. Further down, we entered the territory of the saguaro cactus.

Saguaro cacti are icons of the American southwest. They can grow more than 40 feet tall and are known for the arms that sprout from their thick, fleshy, spine-covered trunks. They can live for nearly 200 years, and by the time they grow their first branches, they’re already over 70 years old. Saguaro grow slowly — in their first 10 years of life they might only become one inch tall. They are thick and rounded and look huggable in the way bears do.

While the classic saguaro cactus has a trunk and two arms, looking happy and vaguely anthropomorphic (as though a cowboy hat should adorn it), they come in all forms. When I witnessed them, I both recoiled in body horror and admired their dignified resilience. Some have gnarled, twisted arms that stick out straight or curve downward, or arms that come in clusters of so many that they look like Hindu gods. Some are covered in dark holes made by the birds that nest inside them. Some are turning black or gray. Some are crested at the top, mutated, as though their brains split open and kept growing into the outside air. Saguaros are propped up internally by woody ribs, so that when they die and their flesh deteriorates, they leave behind a skeleton.

Saguaros are only native to the Sonoran desert — southern Arizona, parts of Mexico, a sliver of California. But these legendary cacti anatopically occupy the cultural imagination of numerous places where they are not native; where they don’t actually exist. The Wikipedia article for saguaro notes that the logo for the Tex-Mex food brand Old El Paso features saguaros, even though “no naturally occurring saguaros are found within 250 miles of El Paso.”

As we drove down past Phoenix, we spotted our first saguaros dotting the rolling hills. Tall, narrow, unmistakable. Within three miles, one or two became a sea of hundreds, standing sentry as we entered their territory. I felt awe in their presence and wondered if this is what is meant by the concept of “fearing God.” A part of me felt welcome into a holy land, another felt like I was trespassing.

Tucson

In Tucson, I spent as much time in the sunlight as possible. I also visited the University of Arizona’s Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, which studies dendrochronology. A massive slice of a Giant Sequoia was on display, 10 feet wide, the core ring dating back to the Roman empire (212 AD — 1,812 years ago). I also learned about the creosote bush, a common shrub that forms clonal colonies. One colony has existed for more than 11,700 years in the Mojave Desert and is among the oldest living organisms on Earth. When it rains, creosote bushes emit an aroma that, apparently, fills the entire city of Tucson. On our next hike, we cupped a sprig of creosote leaves with our palms, exhaled hot air to moisten its leaves, and sniffed. It smelled sharp and herbal.

We ate at La Indita, which featured Mexican, Tohono O’dham, and Purépecha cuisine. I had fried tacos filled with spinach and a green corn tamale. At Tumerico, a vegan Mexican spot, I also filled up on corn and beans, and three salsas: one fruity, one smoky, and one sweet like green chutney.

At the U of A Poetry Center, I sat in on a class about migration. We were told to write creatively about the concept of “arrival.” I wrote about the saguaro cactus (see below). At that night’s poetry reading, three Latinx poets recited poems about three different experiences: translating Indigenous Mexican songs, growing up in a copper town in Arizona, and being Latina in New York.

Let me try to write a poem. Let me try to be like the saguaro cactus — gnarled, soft, ugly, beautiful, grand, twisted — comfortable in its body and physicality, cresting at the head, like when my forehead tingles, standing in a sea of its peers and speciesmen, welcoming travelers into its land, rising ominously over the brown hills, replacing shrubs and overshadowing grasses. Let me be as tall, with as good posture, with as strong limbs, with as spines, with as flesh.

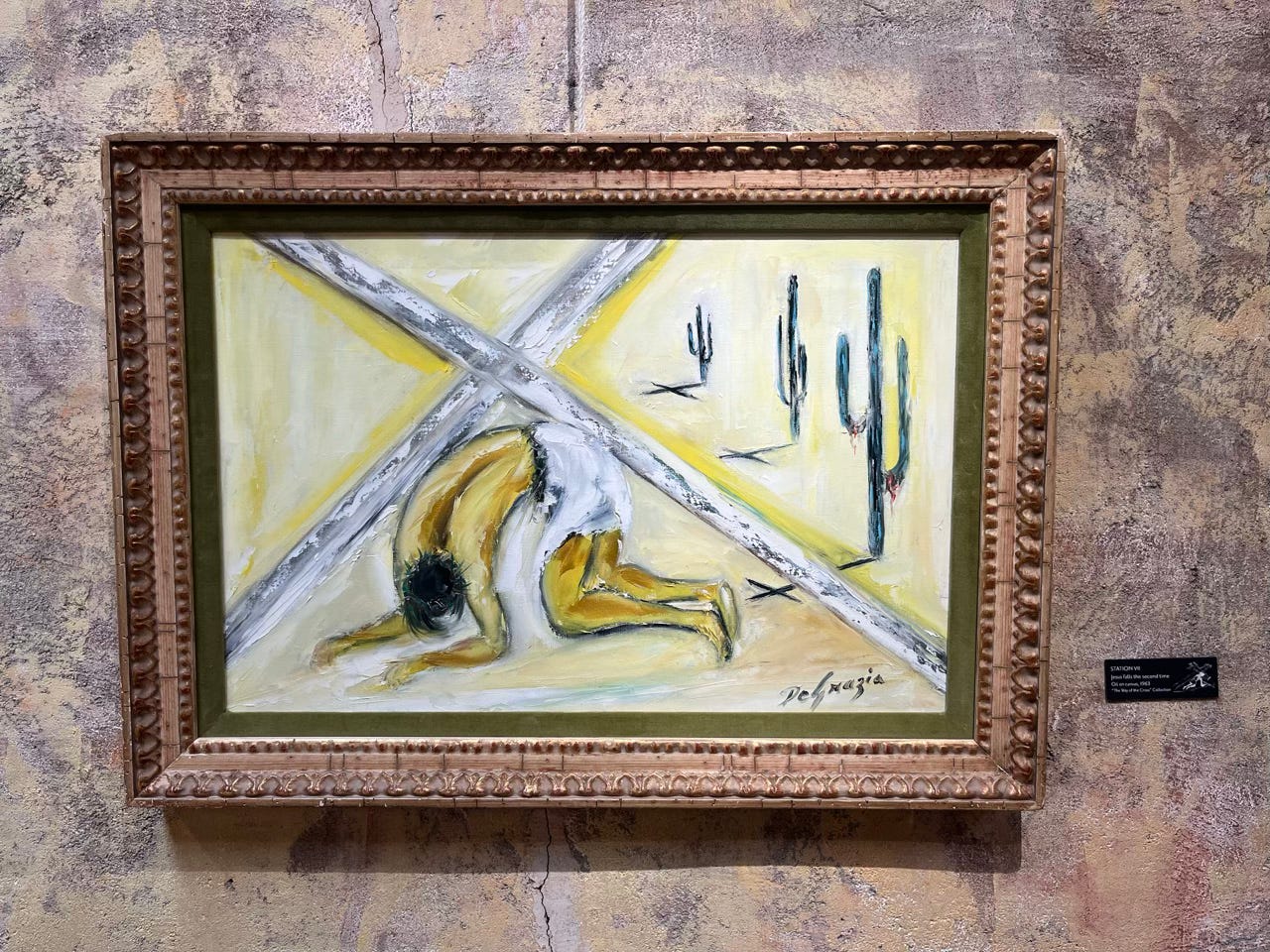

We went to the DeGrazia Gallery in the Sun, a set of buildings designed and built by, and housing the artwork of, Ted DeGrazia. DeGrazia, the son of Italian immigrants, was deeply inspired by Tucson. His paintings were dynamic, colorful, religious, inspired by Native Americans, and evocative of the desert southwest. On site there was a chapel with an open-air roof and a cross made of wooden saguaro ribs. In 1976, DeGrazia staged a protest against the government’s imposition of an inheritance tax on the artwork that he would bequeath to his heirs: He climbed up the Superstition Mountains outside of Phoenix — shrouded in mystery by generations of Indigenous legends — and burned over 100 of his paintings.

The trip ended on the day of the full moon in Virgo, and with one final reverence of the saguaro cacti. My hiking sneakers were still coated in Sedona’s red rust. In Saguaro National Park, Aria and I admired the abundant creosote bushes for us to sniff, barrel cacti that looked like sci-fi worms tunneling out of the earth, and green-skinned palo verde “nurse trees” sheltering young saguaro (still likely older than us). We saw some dead saguaros, skeletons exposed, and wondered out loud — if the cactus is filled with wooden ribs like a tree, what does its root system look like?

Moments later we came upon a fallen saguaro. It had toppled over, turned black at the bottom, and part of its arm had cracked. Its roots, wooden like a tree’s and encased in dirt, were exposed and facing toward us. We admired it. We mourned it. We stepped over it to continue on the trail. The cactus had answered our question even after its life had ended.

I asked about their UFO-related offerings, but unfortunately, they only had a paid tour that we didn’t have the time for.

Thanks for sharing, sounds like an amazing time!

Vivid enough to transport me there, thank you. Especially liked, "Nothing felt manufactured about the hikes"